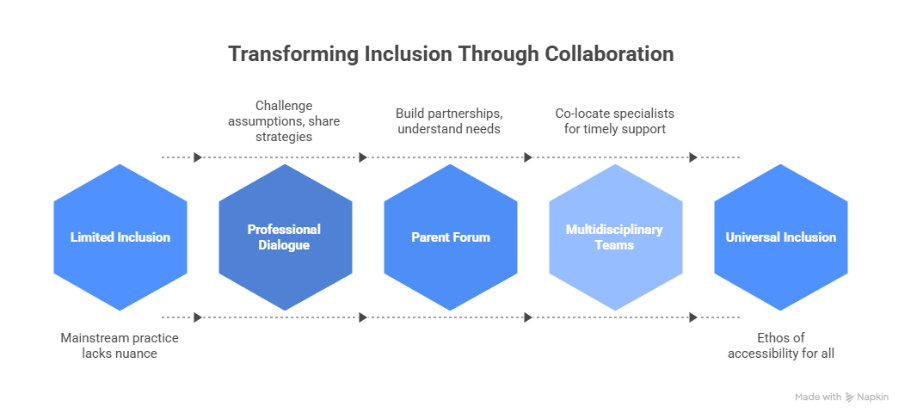

After 30 years in education, I thought I had a good grasp on inclusion. I was wrong. A few years ago, our Trust (Discovery) made a deliberate decision to bring special schools into our fold. This move has transformed how we think about teaching and learning in all our schools. By partnering with special schools, we uncovered blind spots in our mainstream practice and became far more inclusive as a result.

When we first expanded from mainstream to include special schools, it wasn’t just a structural change, it was a mindset shift. We discovered that a lack of inclusion was often rooted not in ill will, but in lack of continuous professional development (CPD) and precious little time for colleagues to reflect on diverse pupil needs. In hindsight, many of us in mainstream simply didn’t know what we didn’t know. We had been “getting by” with surface-level differentiation, unaware of how much more nuanced true adaptation could be.

Working closely with colleagues from special schools was a revelation. Through joint training sessions and informal chats alike, we engaged in high-quality professional dialogue that challenged our assumptions. I remember one discussion about a pupil who frequently refused to work. In the past I might have labelled this as misbehaviour. But my special school colleague helped me see it differently, after observing him, we realised his refusal was often a mask for fear of failure. A simple strategy of offering written and visual instructions, something routinely done in special schools, suddenly turned things around for that pupil. This kind of exchange happened again and again. It dawned on us that adaptation is far more nuanced than we mainstream folks had realised. It’s not just about big interventions; it’s dozens of small adjustments, from how we phrase feedback to how we organise a classroom space, that together make learning accessible to every child.

These changes were transformative. Some were so simple, we wondered, “Why didn’t we always do this?” For example, we started paying attention to the language we use when talking about children. Instead of saying a pupil “is ADHD” or “is low ability,” we now talk about what the pupil needs. This subtle shift sets a tone of possibility, it reminds us (and the pupil) that a label doesn’t define them. We also grew more attuned to the challenges pupils face outside academics. Teachers began routinely using sensory breaks and visual schedules learned from special school practice, and we saw anxious or easily overwhelmed pupils in mainstream settings start to flourish. It felt like unlocking new potential in learners we’d been inadvertently leaving behind.

Crucially, we also brought parents into the conversation in a new way. We established a Parent Forum that meets regularly, something our special schools had modelled. At first, I worried this might become a venue for complaints. But it’s been the opposite, it built stronger partnerships. Parents’ voices were eye-opening. One parent shared how, before our Trust’s changes, they had spent years requesting support for their child’s needs, only to feel ignored. Hearing such stories face-to-face, our staff developed a deeper empathy for the long-term frustration that can build up in families. It wasn’t that teachers didn’t care before, but we hadn’t fully felt what it’s like on the other side of the table. Now, when a parent is upset, we respond with more understanding, we’re quicker to ask, “How can we work together?” rather than getting defensive. That shift alone has defused tensions and aligned everyone around the same goal. We all want the best for the child, that was always true, but now it genuinely feels like “we’re in it together” with families.

On a personal level, the biggest change for me has been a humbling one. I’ve come to realise that delivering high-quality pedagogy is synonymous with meeting the needs of all pupils, not just those in the middle, not just those who fit our old notion of “mainstream”, but every single learner in the room. Partnering with special schools has been deeply rewarding and revealing in this regard. I only wish I had experienced this level of collaboration earlier in my career. It’s frankly a shame that it took over three decades for me to work so closely with special school experts; I can’t help wondering how many pupils in years past might have been better served if I’d known then what I know now.

This journey has convinced me that we need to tear down the remaining walls between “mainstream” and “special”. Inclusion shouldn’t be dictated by the type of school a child attends, it should be a universal ethos. Going forward, I believe we need more overt partnerships at every level of the system. For example, our Trust is advocating for initial teacher training (ITT) programs to include substantial experience in special school settings. How powerful would it be if every new teacher spent time in a special school, honing those adaptive skills from day one? Similarly, we’re creating opportunities for our experienced mainstream teachers (UPS and others) to do mini-placements or exchanges in special schools, and vice versa. The cross-pollination of skills and ideas benefits everyone, our teachers come back brimming with strategies, and special school staff gain insight into mainstream constraints and creative workarounds. It’s a two-way street of learning.

As we await the new national SEND reforms (the upcoming White Paper) planned for early this year, my hope is that it will encourage and support this kind of genuine partnership. However, regardless of policy, we in schools don’t have to wait. My advice to fellow professionals is simple: reach out. Visit a special school. Invite a SENCO or specialist teacher for a coffee and a chat about a challenge you’re facing. Create that parent forum you’ve been nervous about. These experiences have been gamechangers for us at Discovery. They prompted us to reflect on our own practice and find new ways to improve.

Most importantly, they rekindled the joy and moral purpose of why we all became educators – to see every child flourish.

And when you see formerly marginalised pupils light up with success because of changes you’ve made, you’ll wonder, just like I did, why we didn’t do this all along.

The 2014 ‘Risk’ That Became Essential

Back in 2014, we took what felt like a bold step: we employed an Educational Psychologist to improve access to timely, evidence informed support. At the time, it seemed a risk to bring that expertise inhouse rather than relying solely on external capacity. In practice, it proved catalytic. Over time, this evolved into an Educational Psychology team that now provides:

- Rapid consultation and problem solving with school leaders and SENCOs

- Training and coaching for teachers and support staff on assessment, formulation, regulation, and effective classroom adaptations

- Proactive contribution to strategy, shaping Trust wide approaches to inclusion, behaviour, attendance, and SEMH

What once felt experimental is now an essential resource our leaders rely on weekly to unlock barriers, prevent escalation, and sustain inclusive practice. The proximity of the team shortens the distance between concern and effective action, and it keeps expertise circulating within schools rather than disappearing once a report is written.

Why the Future of MATs Is Multidisciplinary

Looking ahead, I’m convinced that MATs will need to create multidisciplinary teams to meet pupils’ increasingly complex needs and to support leaders’ decision making at pace. Educational Psychology is a cornerstone, but the principle is broader: collocated, collaborative specialists (e.g., EPs, therapists, inclusion leads, attendance and safeguarding specialists, EAL and literacy experts) who work with schools, not just for them.

This model:

- Increases access: leaders and teachers get timely advice without long waits

- Builds capacity: knowhow is transferred through coaching, not just consultancy

- Improves consistency and equity: expertise isn’t dependent on postcode or purchasing power

- Reduces duplication: shared assessments and plans travel with the child across settings

- Strengthens prevention: early, relational support avoids later, higher cost interventions

By Paul Stone- CEO Discovery Trust